It’s the Relationship that Heals

By Stuart Copans, MD

The two most common complaints I hear from child care agencies are that there aren’t enough child psychiatrists to see their clients and their clients are on too many medications. The most common complaints from child psychiatrists are that they feel unconnected and excluded from treatment teams, and that time constraints, record keeping requirements, and electronic medical record (EMR) systems interfere with their ability to develop and establish a relationship with their patients.

Although we plan to address these problems separately in future issues of The New Circle, they all are connected to one central problem. Our medical care systems and service delivery models are developed by administrators rather than those who are actually taking care of patients. As a result, the focus is on cost containment, productivity, and efficiency. Patients and clinicians are seen as interchangeable parts, and the importance of long-term relationships is ignored. Also ignored is the relationship between colleagues, which is just as important as the relationship between helper and child. To my mind, it is small wonder that the rate of burnout, early retirement, depression, and suicide among physicians and psychiatrists continues to rise.1

When I began practicing child psychiatry some 40 years ago, the treatment team consisted of a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, and a psychologist, along with other individuals involved in the patient’s care. As a result of the (then) pioneering work of Steven Scharfstein and Gordon Harper, parents were included in the treatment team.2 Increasingly over the last 20 years, as a result of managed care and budget cuts and the emphasis on psychopharmacology, doctors are largely excluded from treatment team meetings, and often nurses are as well.

JUST THE FACTS, MA’AM

Electronic Medical Records (EMR) systems are designed by administrators, not clinicians. They have been promoted as the most efficient way to document in one place all the costs associated with a patient’s care. But in my view—and the view of many of my colleagues in the medical profession who live with the system’s “efficiencies” in their everyday practice—the first goal of EMR is to document what is needed in order to charge as much as possible; the second is to document what is needed to pass accreditation surveys; and the third goal is protection in case of a bad outcome and lawsuit. The least of EMR’s priorities is gathering the information a doctor needs to take care of a patient. As Sergeant Friday used to say in that old TV show Dragnet, “Just the facts Ma’am, all we want is the facts.”

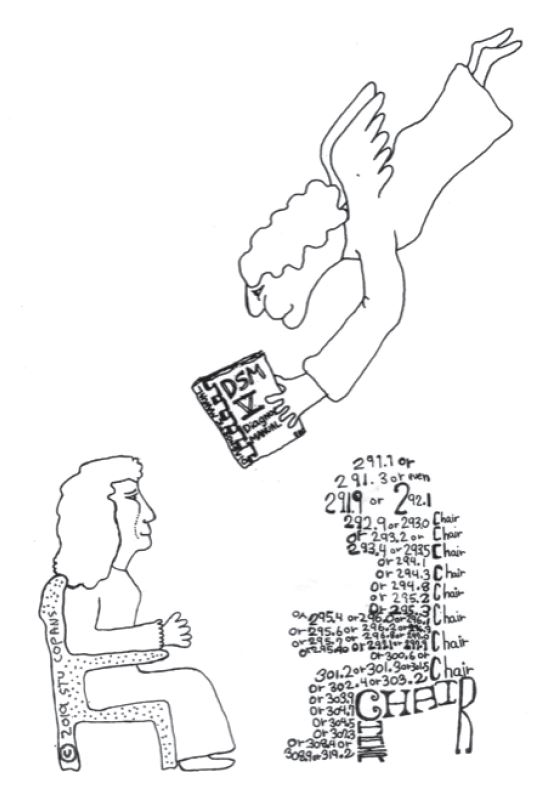

In 1977, in our book, Who’s the Patient Here, a humorous take on learning to do psychotherapy, Tom Singer and I pointed out that one of the common mistakes early-career therapists made was seeing the patient as an illness not a person.

What was a mistake often made by new therapists is now reified, sanctified, and objectified by insurance companies, accreditation agencies, and the health care organizations that depend on them for their funding and licensing. And the first criterion for listing diagnoses is often whether or not they are reimbursable. Those of us working with troubled youths are all working in a field called human services, and yet we are often working with them in ways based on industrial models of production that are not designed for helping children grow and change, but rather treating them as identical parts on an assembly line.

Although universal health care coverage is an important goal, it will not solve the problem created by imposing an industrial model on human services. The solution is a medical care system that focuses its efforts on and through the family and community. How we can do that will be the long-term focus of future articles by myself and my colleagues in the field of child psychiatry. Future articles will address some of the following issues:

• What it takes to attract and keep staff (at all levels)

• Polypharmacy, it causes, its uses, and its dangers

• Primum non Nocere—what we do in treating children that may do more harm than good

• How to do what funders expect without it interfering with treatment

• The importance of getting feedback from people we have treated after treatment is finished

• Dealing with failure—no one can help everyone. Not recognizing and accepting that fact can lead to bad treatment

• Working with families, no matter who is the identified patient

• Strengthening the health-promoting capacities of natural communities

- Shanafelt T, West C, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017 [published online February 22, 2019]. Mayo Clin Proc. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023.

- Harper, G. (1989). Focal inpatient treatment planning. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Vol 28, 31-37. Harper, G., & Irvin, E. (1985). Alliance formation with parents: Limit-setting and the effect of mandated reporting. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55, 550-560.

Stuart Copans, MD

Stu works as a child psychiatrist, cartoonist, papercutter, pataphysician, mailartist, writer, illustrator, and small book publisher, and has written and illustrated books published by major houses. He graduated from Harvard College, earned his medical degree at Stanford, and did his training in psychiatry and child psychiatry at NICHD, GW, UVM, and Dartmouth. Stu currently teaches child psychotherapy at Dartmouth, and evaluates and treats patients in residential care and hospital diversion programs. He was elected to membership in the Group for Advancement of Psychiatry where he is currently a member of the research committee. Stu and his wife Mary have lived in Brattleboro since 1977. They have 4 children and 10 grandchildren. Stu tries not to take himself too seriously, but according to his wife he lapses frequently. His current interests are collaborative processes, therapeutic interactions, and the therapeutic effects of humor and art.