Traumatic Brain Injury in Justice-Involved Youths: A Call to Action

by Danielle Ciccone-Coutre & Dawn Pflugradt

Read this article offline by downloading the PDF version here.

A

recent article (2022) published in the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

highlighted an upcoming study in Florida that focuses on gauging the prevalence

and impact of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in justice-involved

youths. In this projected three-year-study, aims include determining which treatments might help those youth complete their education, succeed at work, and prevent them from cycling in and out of detention.[1]

In the last five years, there has been increased attention on TBIs in children and adolescents. For example, in 2018, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) sent a report to congress titled: The Management of Traumatic Brain Injury in Children: Opportunities for Action. In this report, the CDC asked for head injury in children and adolescents to be considered a public health burden in the United States.[2]

A TBI is an acquired injury that can disrupt functioning. Traumatic brain injury can occur due to a bump, blow, jolt, or penetration to the head. Children and adolescents are already in the midst of critical developmental periods of growth and maturation, leading to increased vulnerability for the potentially negative impact of a TBI. As many of us who work with juveniles know, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that occur during the developmental period, have been well researched and recognized as having lasting impacts on functioning in adulthood. As such, we assess for the presence of ACEs with clients. Similarly, TBI, particularly when mild in severity, is one of those “invisible injuries” that needs to be included in the assessment, treatment, and management of risk.

Per the CDC, children have one of the highest rates of TBI-related emergency room visits for reasons including falls, motor-vehicle crashes, as well as sports/recreation-related injuries. Also specific to children and adolescents is abusive head trauma (AHT) defined as “a preventable and severe form of physical child abuse that results in an injury to the brain of the child.”[2] An injury of any level severity—mild, moderate, or severe—can have a significant impact on the developing brain and “can disrupt the developmental trajectory.”[2] Although children typically recover physically, longer lasting effects can be significant and can impact upon academic achievement as well as healthy social engagement, which can lead to more pervasive problems, including involvement with the criminal justice system. Further, labeling the symptoms of a TBI as behavioral or even a personality-related concern can lead to a youth not receiving appropriate services and interventions. This is even more problematic for youths who are already marginalized.

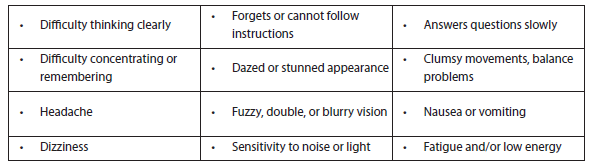

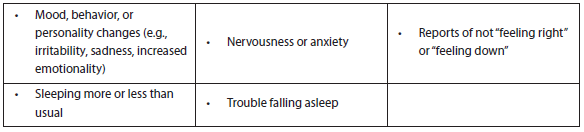

The table below includes common symptoms that are seen after a mild TBI.[2] These symptoms can certainly overlap with other cognitive, physical, mental/emotional health, and sleep issues, complicating the plan for intervention.

As previously stated, these symptoms may often be mislabeled (i.e., attributed to a behavioral problem or other DSM-5-TR diagnosis) in justice-involved youths, when in fact justice-involved youths are three times more likely to have experienced a head injury than the general population.[1] Therefore, individuals working in the criminal justice system are urged to use evidence-driven assessment tools and interventions to assist in identification and treatment of TBI. Renn & Veeh (2017) provide basic guidelines, including administration of a more thorough assessment, such as the Ohio State University TBI identification (OSU-TBI-ID) method and/or the traumatic brain Injury questionnaire (TBIQ). Further they recommend asking about potential head/neck injuries, as it is purported that 85 percent of TBIs are never documented, due to lack of medical intervention (possibly due to limited access to healthcare for marginalized individuals). When individuals do not receive medical attention or do not experience a loss of consciousness, we often overlook the possibility of a mild head injury, which can have lasting dire consequences. As concluded by Renn & Veeh (2017), “We have the tools to address TBI. We must act.”[3]

In response to the increased attention on TBIs in children and adolescents, the National Partnership of Juvenile Services (NPJS) developed a position statement related to identifying and responding to youths with brain injuries within the juvenile justice system. It reads:

The National Partnership of Juvenile Services (NPJS) strongly advocates that juvenile justice professionals have adequate resources to meet the needs of youth with brain injury, including; staff training, validated tools for screening, and intervention strategies to address associated behaviors, as well as access to trained education staff and/or local school districts to assist in providing appropriate educational supports. Additionally, brain injury specialists must be accessible to assess youth identified as having impairments as a result of brain injury to determine specific rehabilitation treatment needs. Local resources must be identified that can offer support, intervention, and/or treatment to address associated impairments while youth with brain injury are in custody and upon return to their community/home. Additionally, services that are designed to address recidivism as well as cognitive academic supports must be tailored for youth with impairments from brain injury

The full position statement, information related to its development, as well as other initiatives for justice-involved youths can be found at: https://www.npjs.org/our-work/position-statements.

Concluding, children and adolescents are one of the most vulnerable populations at risk for potential head injury. Therefore, anyone caring for and/or working with this population must learn more about this public health burden. It is hoped that by promoting education and awareness of TBI and its inter-related patterns of symptoms (e.g., behavioral, emotional, physiological, and cognitive), clinicians, parents/guardians, and caseworkers will be able to effectively identify issues and provide targeted individualized responses to youths in order to prevent lifelong consequences. Specific to justice-involved youths, without proper identification and treatment, the revolving door of the criminal justice system is likely to continue.

Below are some helpful resources and additional information about TBI in youths:

End Notes

[1] Danney, M. [2022, January 18]. Upcoming Study aims to gauge prevalence and impact of traumatic brain injury on juveniles in detention. Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. https://jjie.org/2022/01/18/upcoming-study-aims-to-gauge-prevalence-and-impact-of-traumatic-brain-injury-on-juveniles-in-detention/

[2]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Report to Congress: The Management of Traumatic Brain Injury in Children, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Atlanta, GA.

[3] Renn, T., & Veeh, C. [2017, June 26]. Untreated Traumatic Brain Injury Keeps Youth in Juvenile Justice System. Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. https://jjie.org/2017/06/26/untreated-traumatic-brain-injury-keep-youth-in-juvenile-justice-system/

About the Authors

Danielle Ciccone-Coutre is a Board-Certified Rehabilitation Psychologist. She currently serves as the Chief Regional Psychologist for the Department of Corrections (DOC)/Division of Community Corrections (DCC) in Southeastern Wisconsin. Her career foci have included predominantly, work with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder across the developmental lifespan. She is committed to the education and advocacy of TBI to promote awareness and implement change to support survivors, and those involved in their care. She spearheads and supervises research of TBI and interrelated disabilities in the Veteran’s Administration. She is also collaborating on research in the DOC/DCC, with interest in the role of TBI, and neuro/rehabilitation psychology of criminal behavior. Dr. Ciccone-Coutre serves on the Board of Directors for the Brain Injury Alliance of Wisconsin. She also maintains a private practice in northern Illinois.

Dawn Pflugradt is a licensed psychologist specializing in forensic and clinical psychology. She has advanced degrees in psychology, social work and bioethics. She works as a Risk Assessment Specialist for a Midwestern Department of Community Corrections and maintains a private psychology practice. Dr. Pflugradt is also a professor at the Wisconsin School of Professional Psychology. Further, she serves on the scientific advisory board for the International Association for the Treatment of Sexual Offenders (IATSO) and is a SAARNA certified STATIC-99R and STABLE-2007 trainer. In addition to her years of clinical experience, Dr. Pflugradt has published books, numerous articles, and book chapters in the areas of pediatrics and criminology.