The Complex (But Crucial) Context of Families

By David V. Keith, MD

In the previous issue of The New Circle, Stu Copans said there is no such thing as a child. Similarly, I don’t believe in individuals. An individual is a fragment of a family, in the context of family life.

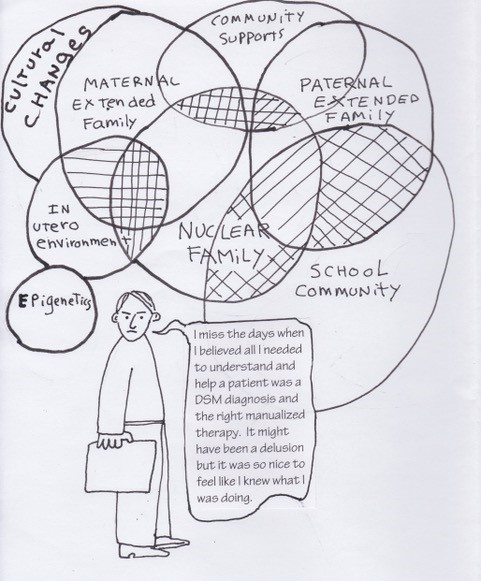

As a “family psychiatrist” my work is grounded in systemic thinking, which provides a different way of thinking than conventional psychiatry. It has much more room for imagination. In my work, I always begin with the whole family, and what emerges from an interview with the family is often an uneven, lumpy woven fabric. Indeed, the etymology of “context” refers to joining together or weaving.

Clinical Illustration

When Kristin was 17, a high school senior, her father called for an appointment. I could hear his distress. “My daughter is out of control. She has bipolar disorder. She stopped taking her medication four months ago. I knew this was going to happen.”

I told John he would have to bring the whole family. That is the way I engage with, not just the symptomatic person, but their multi-personal context, in which interviewing a family is different from interviewing an individual. Given John’s urgency about his daughter being “out of control,” I arranged to see them the next day. The whole family came: mother, father, Kristin, and her 14-year-old brother, Brad.

The Kristin who attended this first meeting was very different from the one I had expected. Instead of disturbed and chaotic, she was composed and thoughtful in an appealing and graceful way. She was a self-owning young woman who agreed she had been difficult of late, but was annoyed with what she viewed as her parents’ over-reactions. Surprisingly, she was far more capable of self-observation than either of her parents, who were tense and agitated in contrast with Kris. In answer to my standard first question, “How can I help?,” the parents began an inventory of Kris’ objectionable behavior, reviewing all she was doing that disturbed them. Unlike most adolescents in that situation, Kris did not become defensive or reactive.

History as Context

History is part of context. Once I had learned enough about Kris, I asked her about family life. She said her parents were both depressed, and added she was trying to make certain she did not grow up to be like them. When I asked John to tell me what the family was like, he fumbled with the question. He knew how to talk about Kris’ misbehavior, but did not have words for relationships. Dressed in suit and tie, John came across as conservative and repressed, not good at paying attention to his interior life. He said Kris had quit her medications the preceding October, soon after he, a corporate executive, had lost his job; he said it was not a “big deal, just a business decision.” He seemed to be relieving any uncertainty he felt about himself by becoming angry with Kris or his spouse.

When Kris was 4, she had been taken to see “the best” child psychiatrist in the city, following her mother’s increasing distress. The doctor decided Kris had bipolar disorder and that she “deserved” a trial of lithium, and she had been on a variety of medications ever since. The diagnosis was made in the era when bipolar disorder was the diagnosis du jour in child psychiatry. In the doctor’s chart, there was virtually no information about the family, and no note about the mother’s distress. The chart described his interview with Kris, noting that she did not misbehave in his office, then listed the symptoms described as present by her parents—especially her mother. But, basing his diagnosis and prescription of medication on the parents’ descriptions of Kris’s behavior and the issues Kris’s behaviors and moods raised for the family was, in effect, treating not the child but the parents’ distress. I think the doctor was considered “the best” psychiatrist because he was quick to prescribe medication. He certainly was in tune with the times, basing his diagnostic and medication decisions solely on a strict adherence to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (i.e., “If you have the symptoms, you have the diagnosis.”).

Here is a little more context. After trying to get pregnant for 10 years, Kris was born. Her mother, Carol Marie, had decided she was unable to have children, so Kris’ birth had a profound effect on Carol Marie’s sense of who she was. She gave birth to Brad three years later. Another blessing, but with two children, life becomes more complicated.

Some of that complication, however, was related to another part of the context: John—how he grew up, how he learned to be a person. John’s father ran a successful retail business in a small city and John learned his business skills from working in his father’s store. His mother was an angry harsh woman, and John became distressed by angry or upset women. A corporate success, John was difficult at home. Carol Marie had her hands full with two little children, and was sometimes emotionally drained when John arrived home from the office. But when faced with her upset, John became angry and reactive, not knowing how to offer comfort. Instead, he felt she was imposing unreasonable demands and would become angry, demanding. He would yell at her to keep quiet: “I hate it when you get so emotional,” and “Keep those kids quiet,” and “ Dammit! You didn’t iron my shirt.” In our sessions, John, visibly uncomfortable, said, “I should have been more understanding.” Carol Marie, remembering this painful time, said softly, “I felt overwhelmed, isolated, and incredibly lonely,” feeling distressed and alone with the kids. In turn, her distress distressed Kris, then 4 years of age, who began to be naughty and upsetting. This child, who had taught her so much about loving when she was an infant and toddler, was now disappointing Carol Marie by being oppositional and sassy. A naughty child takes care of a depressed mother by arousing her anger. It is hard to be angry and depressed at the same time.

Kris’ parents stuck with the idea that she had bipolar disorder, and her pediatrician continued the medications. While they described Kris as “out of control,” I found her to be a young woman in her last year of high school whose mildly defiant behavior was in part her attempt to escape the restrictions of being mother’s little girl and unable to be herself. Afraid she would turn out like her parents, Kris wanted her mother to meet the mother of a friend: “She knows how to laugh. My mom doesn’t. She would be a good friend for my mom.”

Kris went to college at the end of that summer, where she did well, later graduating with a degree in business. During the preceding six months, our family therapy sessions included discussions about the marriage and family behaviors. Although 14 year-old Brad was engaged, he said little to make waves during the course of therapy, but it was clear that he had close relationships with his mother and sister. Dad was the odd man out. In fact, John was embarrassed by many of his behaviors, and he took steps to participate more. Kris helped him learn to do the laundry. A quantum leap. The whole family celebrated his achievement. Kris’ diagnosis of bipolar disorder seemed a distortion, remaining in place for far too long. She had stopped taking her medications, and nothing during our six months of therapy suggested they should be restarted.

A month after Kris left for college, Carol Marie called, wanting to see me alone. She had dropped “Marie” to become a less saintly “Carol,” and she did a number of things that reminded me of what had been considered misbehavior in her daughter. She also considered buying a small café in their town. About a month after our last session, Carol called to tell me she had bought a new pick-up truck. It was as if Kris had become a role model for breaking out of patterns. Carol even thanked Kris for teaching her how to surprise herself.

A great deal is woven together in this brief sketch of this patient’s story, in which I am describing only a few of the interwoven strands that formed the family context and help us more clearly see and understand.

Why Context?

I hope I’ve provided a sense of the relevance and importance of context, and how it works in understanding a patient’s behaviors, and in this case in relation to a psychiatric diagnosis. Context is a knitted weaving, often overlooked by medical practitioners, in which an empirical approach alone does not work well in understanding the contextual histories of their patients. By recognizing family context and working with family dynamics, I was able to help all the family members improve upon their lives. The outcome of the approach used by Kris’ former prescribing psychiatrist was focused upon only the behavior of a 4-year-old child without context, resulting in years of unnecessary medication for the child, and contributing further to dysfunction for the child’s family. However, learning about context in a family interview, and making use of it in family work, is an art. Its rudiments can be taught, but it is better learned from experience. In dealing with context, imagination is a crucial part of our practices.

Although providing only fragments of a complex case, I hope this article is nonetheless illuminating, addressing the importance of recognizing context and its role in both understanding and in the delivery of services.

David V. Keith, MD

David Keith is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY. He was in practice for 44 years, joining the Psychiatry Department at SUNY Upstate Medical University in October 1988. His clinical work has always been organized around teaching, supervising and practicing psychotherapeutic work with multigenerational families. His work focuses on families with chronic illness, whether the illness resides in the body, the mind or the relationship system. He views himself as a medication minimalist. He is intrigued by language and how it shapes our perceptions, but more specifically how language is used to represent illness, by patients and practitioners, and ultimately how language can be used therapeutically.

He coauthored Defiance in the Family: Finding Hope in Therapy (2001), co-edited, Family Therapy as an Alternative to Medication: An Appraisal of Pharmland (2003) and is the author of Continuing the Experiential Approach of Carl Whitaker: Process, Practice & Magic (2015).