What is Social Work – And Who Exactly are Social Workers?

By Katelen Fortunati, DSW LCSW

In the social work articles of the The New Circle, social work professionals will share problems and insights regarding their work with at-risk children and adolescents. But because social work is such a broad and varied helping profession, in this inaugural issue of the magazine, we will address the simple, but basic question: “What is social work and who exactly are social workers?”

The modern social work profession is difficult to describe because we work in so many different arenas—child welfare, education, policy making, criminal justice, hospitals, community organizing, nursing homes, community-based mental health centers, substance abuse centers, military bases, private practice, hospice, and so many other important spaces.

Although in today’s world our day-to-day work is varied, our history is common. Before we explore innovations in social work practice with at-risk children and adolescents in forthcoming issues of this magazine, we need to have a basic understanding of the enormous impact that the past has had on our profession. Many of the challenges social workers face today are the result of: (a) society’s perceptions of the needs of the populations we were directed to serve, and (b) the laws that dictated our purpose and how we were to operate.

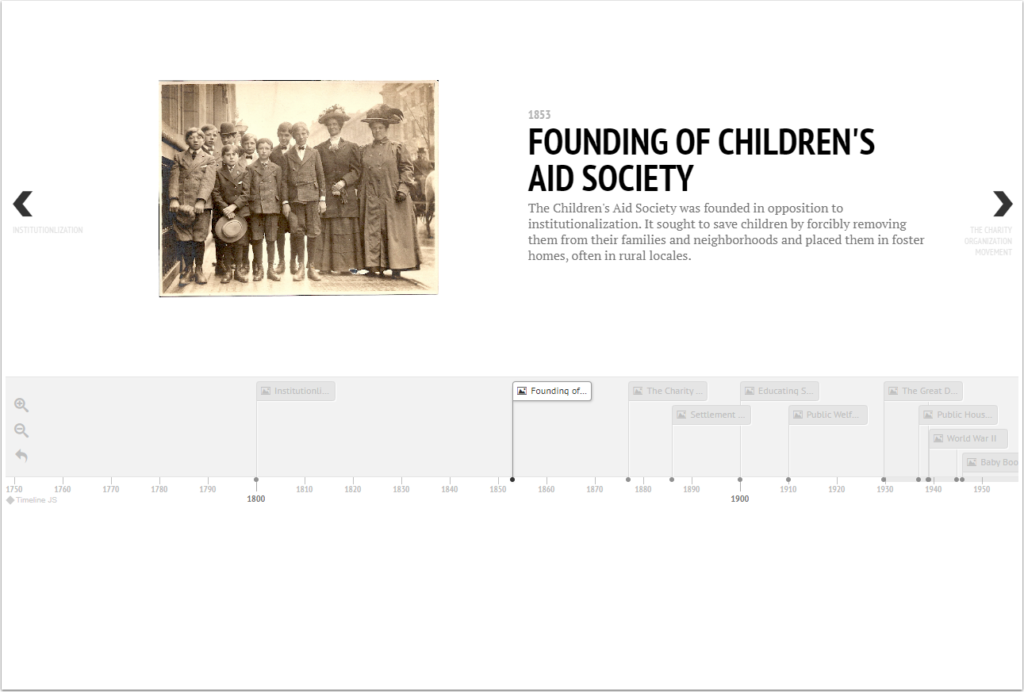

To help our readers who are professionals in fields other than social work understand the ways in which modern social work functions in regard to at-risk children, let us pause here for a brief history lesson about how the social work profession developed in the United States, and how it has been, and continues to be, impacted by changing social mores and political events. Click on the image to view the entire interactive timeline I developed to accompany this article. It encapsulates the five-century history (that’s right, 500 years) of the societal changes and political events that have shaped the field of social work.

Who Were We Then?

Originating in volunteer efforts for social betterment in the late 19th century, social work became an occupation in the early 20th century and the professionalization of social work began in the 1920s. But until the 1990s, and more recently, and especially in low-income areas of the country, social workers were often perceived as representatives from the government who take poor people’s kids away. Supporting the notions of distrust in these communities until very recently, both federal and state governments have consistently taken the stance that people in the lower income strata, including communities of color and Native American communities, are not to be trusted and the children who come from these communities need strict and intensive interventions to become productive members of society.1

Child “Removal” and Institutionalization as Public Policy

The practice of removing children from their homes or communities was modeled after European practices that the American Colonies adopted as ways to “take care of” children who were homeless, orphaned, or impoverished. In the mid-1800s, prior to the formalization of the social work profession, there was an increase in efforts aimed at institutionalization as the best way to “help” wayward and poor children, leading to the development of orphanages, where many of the employees would today be considered social workers.2

One egregious result of this trend was due to President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830, which mandated that Native American children must be educated apart from their families in boarding schools. This practice went on until the passing of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, when Native American parents were finally given the legal right to refuse boarding school education for their children.3

Foster Care—An Alternative to Institutionalization

Founded in 1863, the Children’s Aid Society opposed institutionalizing children, and sought to save children from institutionalization by instead forcibly removing them from their families and urban neighborhoods and placing them in smaller foster homes in rural locales.4 This practice persisted through the 1940s with Georgia Tann and the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, where children were removed through deception and coercion from poor or homeless families and sold to families who were more financially stable.

The practice of removal continued well into the 20th Century. For example, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974 encouraged the practice of removing children from their families of origin that were vagrant and/or poor—particularly non-white children—and placing them in foster care. Many of those conducting these removals were individuals considered to be social workers or social service providers.

Who Are We Now?

Social work history has not always been a glowing success story; nevertheless much good has happened and is happening because of social workers. We are agents of positive and creative change. We are helping the nearly 7.7 million children impacted by a mental health disorder in America. Through our positions in the community, schools, hospitals, and community mental health centers, social workers are often first responders to the needs of children who are experiencing traumas associated with community, school, or family violence, parental incarceration, natural disasters, and more. We are on the front lines providing critical mental health care to the approximately 47.6 million American adults who are facing a mental health disorder. We are helping those who are captive in human trafficking situations. We are helping to improve the financial outcomes for families. We are supporting those impacted by deportation and immigration changes. We are representing constituents, leading school districts, producing media, working against inequalities and for civil rights, and disseminating knowledge through our writing. We are social innovators.

HOW ARE SOCIAL WORKERS TRAINED?

The approximately 800,000 social work professionals in the U.S. today have different levels of training and degree programs offer different content. Whereas the masters’ degree in social work (most typically, an MSW) is the terminal degree required for independent social work practice, a doctorate in social work (DSW or PhD) is more typically focused on social work research and/or graduate education. Unlike psychology and counseling professionals who must hold at least a master’s degree to practice, those holding a bachelor’s degree in social work (BSW) may also practice as a social worker, under supervised and restricted conditions. A social worker with at least a master’s degree may obtain licensing in the state where they practice as a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW). Clinical social workers may engage in assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental, behavioral, and emotional disorders.

Holding it all together, a standard process for the education, training, and licensing of social workers is uniform across the United States. To learn more about social work degrees and degree programs, visit the Social Work Degree Center, the Council on Social Work Education, or the MSW Guide.

We social workers are a diverse group. There are a lot of us, with much to teach and learn. Our focus in the social work articles of future issues of The New Circle, will be on social work in relation to at-risk children and adolescents, including the challenges of working in low-income communities, dealing with racial and cultural factors and under-funded counseling or educational environments, as well as the innovations and hope for where we can go in the future.

1. Brockie, T. N., Dana-Sacco, G., Wallen, G. R., Wilcox, H. C., & Campbell, J. C. (2015). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly-drug use and suicide attempt in reservation-based Native American adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3–4), 411–421.Curry-Stevens, A., Cross-Hemmer, A., Maher, N., & Meier, J. (2011). The politics of data: Uncovering whiteness in conventional social policy and social work research. Sociology Mind.

Dettlaff, A. J., & Rycraft, J. R. (2008). Deconstructing disproportionality: Views from multiple community stakeholders. Child Welfare, 87(2), 37–58.

Piccard, A. (2013). Death by boarding school: The last acceptable racism and the United States’ genocide of Native Americans. Gonz. L. Rev., 49, 137.

Stern, M. J., & Axinn, J. (2018). Social Welfare: A history of the American response to need. New York: Pearson.

2. Meskell, M.W. (1999). An American resolution: The history of prisons in the United States from 1777 to 1877. Stanford Law Review, 51(4), 839–865. Stern, M.J., and Axinn, J. (2018). Social welfare: A history of the American response to need. New York: Pearson.

3. Piccard, A. (2013). Death by Boarding School: The Last Acceptable Racism and the United States’ Genocide of Native Americans. Gonz. L. Rev., 49, 137.

4. Stern, M.J., and Axinn, J. (2018). Social welfare: A history of the American response to need. New York: Pearson.

Katelen Fortunati, DSW LCSW

Katelen received her Master’s in Social Work from Saint Louis University and her Doctorate of Clinical Social Work from Rutgers. She also received a Certificate in Violence Prevention from Washington University of St. Louis. Her work has focused on helping others understand the ambiguous grief experienced by children with incarcerated parents and the impact of parental incarceration on parent-child attachment. Currently, she is working in Colorado disseminating this information through the public school systems and county corrections through her non-profit organization, Every Single Kid. She is also the author of the ChIPs books for children downloadable free from Safer Society Press.