What Are Helping Professionals Up Against?

By David S. Prescott, LICSW

What happens when, despite all our best intentions and efforts, we aren’t able to fulfill our professional missions? What follows are largely my personal observations from 35 years of practice as a therapist, supervisor, consultant, and administrator.

Who Are We?

I have yet to meet the person working with at-risk children and adolescents who does not have a passionate desire to make a contribution to the world around them. Likewise, I have never met the professional at the front lines who was paid what they are truly worth in the lives of young people. I am not the first to observe that, “We’re in it more for the outcome than the income.” Some recent evidence of this came from California in June 2019. Mental health workers from Kaiser Permanente threatened to go on strike. Central to their demands was patient care and the delay that their clients often experienced while awaiting services1. The same mental health workers had staged a five-day walk-out in protest in December 2018.

In my trainings with professionals serving at-risk young people, I regularly ask how often their clients have sworn at them or otherwise treated them disrespectfully. Nearly every hand goes up. When I ask what keeps them going, the answers are typically that they value their co-workers, understand that the young people they serve face serious challenges, and have generally learned not to take things personally. I have come to wonder, however, whether our commitment to this work is not also a vulnerability—a vulnerability to exploitation by funding sources, whether intended or not.

Where Are We At?

Those of us who have endured life at the front lines of youth-serving organizations are all familiar with the scarcity of resources. Wage and salary rates have not kept pace with the cost of living for many years. State budgets are constantly being trimmed and having to do more with less has been the norm since the 1970s. Added to that are ever-escalating demands from funders for documentation and justification of services. One often has to speak several variations of the English language in order to survive. Being able to converse meaningfully and fluently with both clients and the sources of our funding and licensing—grant-makers, state regulators, auditors, insurers—can be a daunting challenge. Many of us have encountered the situation in which an outside professional with far less knowledge and experience judges the decisions of the professional who actually works with the client whose case the auditor is examining. Scrutiny is increasing; respect and gratitude from outside the field are not. What is the helping professional to do?

In my experience, many consequences of the above circumstances have followed. One is that membership in professional organizations has not kept pace with the times. Early-career professionals are interested in certification programs in specific approaches or areas of practice, as well as anything else that helps them to advance their careers quickly, but these activities tend to be more solitary than team-oriented.

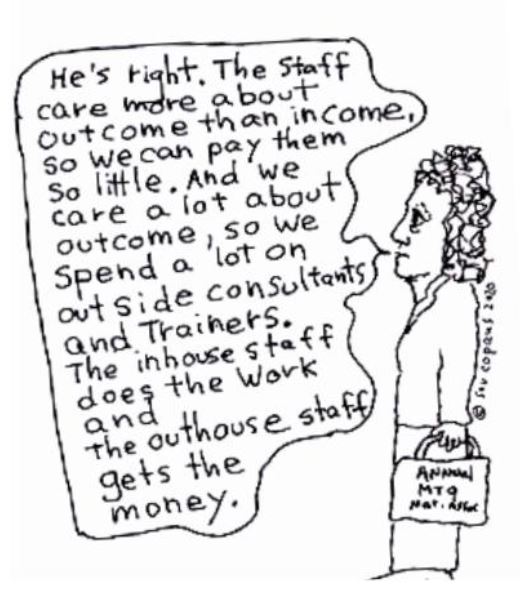

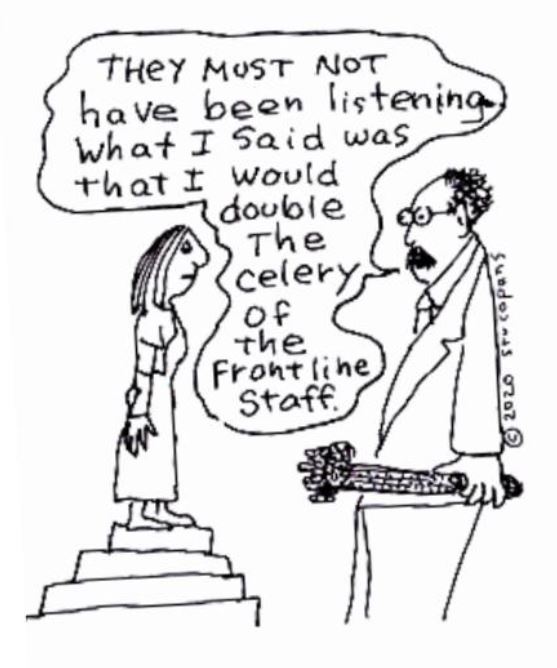

Diminished resources seem to have resulted in professionals feeling less confident that their employers have their backs. Likewise, professional loyalty to employers seems also to have diminished with time. The inevitable result has been individual helping professionals and their supervisors prioritizing their own interests to the exclusion of everything else. This frequently takes the form of increased workforce turnover, adding to a pervasive sense of rapid change that reduces not only loyalty to the agency and its mission, but sometimes deep commitment to a specific client population as well. Add to this the fact that training budgets for employees are often the first cuts to be made and it is not difficult to see why the ecology of social and therapeutic services has changed dramatically.

While resources have shrunk, demands on us to be accountable for our services have exploded. One observer once quipped that, “In the future, we will no longer be able to afford to see our clients, but thanks to our electronic medical records, the paperwork will be submitted on time.” Although effective documentation, like other aspects of clinical work, can be a matter of public health and safety, it seems that outside auditors and licensors often confuse quality of documentation with the effectiveness of the service. While the current ethos of applying a proven solution to a specific problem is welcome, other considerations apply, such as whether or not the client is reporting improvement. Worse, the voice of the client too often goes missing in efforts at quality improvement. Few agencies make it a routine practice to actively seek their clients’ feedback, although there have been encouraging trends in this area.

To this last point, on the importance of client feedback and the experience of the client, one psychologist outside the USA described a harrowing experience. In order to be registered as a psychologist, she had to describe her areas of expertise to the local registrar. She explained that she had extensive training in SolutionFocused Therapy (SFT). The registrar asked what SFT is. The psychologist replied, “It is a kind of person-centered treatment.” The registrar responded, “I’m sorry, but I don’t see person-centered treatment on our list of approved practices.” The same may be true in all areas of human and helping services, in which those authorizing the service, no matter what it may be, may fail to recognize the importance of the relationship between the “technique” and the person being helped by the technique, and the role of the provider, whether an educator, therapist, social worker, or medical practitioner, in applying the technique.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Ultimately, helping professionals want to make a difference, and yet our circumstances all too often make this a dream deferred. So where do we go from here? In this flagship issue of The New Circle, the editors—each of whom works in one of the helping professions— offer details about the general problems I have raised here from the perspective of their own profession and the services they provide. Future issues will be dedicated to sharing ideas and innovations for what we can do as professionals to improve our services and ensure excellent care, in spite of the circumstances and forces that are too often arrayed against us.

- Peltz, J.F. (2019, June 10). Kaiser Permanente mental health workers call off threatened strike. Los Angeles Times.

David S. Prescott, LICSW

A mental health practitioner of 36 years, David is the Editor of Safer Society Press. He is the author and editor of 20 books in the areas of understanding and improving services to at-risk clients. He is best known for his work in the areas of understanding, assessing, and treating sexual violence and trauma. David is the recipient of the 2014 Distinguished Contribution award from the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers and the 2018 recipient of the National Adolescent Perpetration Network’s C. Henry Kempe Lifetime Achievement award. He currently trains and lectures around the world.